There has been loads of chatter and angst lately over the question “Can AI make art?” (Here are a few examples: Ted Chiang in The New Yorker; The Verge; a response to Ted Chiang in The Atlantic; BBC)

But I think a much more important and more immediately actionable question is about whether the current and future media ecosystem can distribute art, regardless of who or what makes it. Or put more simply, “Can TikTok* give us art?”

(*By TikTok, I mean that platform itself, but also the entire realm of algorithmic, personalized feed-based entertainment.)

Intro: Let People Like What They Like

“But the bitter truth we critics must face is that, in the grand scheme of things, the average piece of junk is probably more meaningful than our criticism designating it so.” -Anton Ego, Ratatouille

In his book Status and Culture, W. David Marx argues that the desire to gain social rank is the driving force in the formation of taste, art, fashion, and all the conventions that make up our ever-evolving cultural ecosystem. Acquiring cultural capital is one of the most common means of attaining social status.

As a result, one of humanity’s unfortunate tendencies is to judge other people for what brings them joy. We deride people for liking Adam Sandler movies or reality TV. We especially look down on fans who like something too much, like Disney adults or Trekkies. As economist Thorstein Velben says, “The failure to consume in due quantity and quality becomes a mark of inferiority or demerit.”

The whole concept of “taste” arose in the 18th century as a way for the aristocracy to continue to virtue signal their elite status to the untamed but increasingly wealthy new money bourgeoisie. In the 21st century, since most of us aren’t earls or duchesses or viscounts, we create alternative social systems that enable us to feel that we have superior status through cultural choices, sometimes still economically driven (Eleven Madison Park vs. McDonalds), but more often taste-driven (a $16 movie ticket can let you see an art film or Avengers: Endgame).

Or as Marx (David again, not Karl) puts it, “Whatever fundamental desires to be ourselves, however, must be aligned with our fundamental desire for status.”

As humans, we must balance experiencing the cultural conventions that bring us joy with the expectations and signaling that ensures we don’t lose status. And as media choices proliferate, so do the moments we’re confronted with this tension. Our most immediate assessment of any piece of entertainment is on the spectrum of Bad to Good, usually based on what the upper-middle class/elite populous or critical apparatus would say, instead of simply whether we like it or not. We have a cultural hierarchy, with opera and the symphony and other aristocratic conventions at the top, and Guy Fieri, Danielle Steel novels, and Nickelback at the bottom.

(Of course, some things can overcome their supposed place on the Good-Bad spectrum by gathering enough enthusiasm from the right status groups. There are lots of things that are broadly accepted as great, and manage to be almost universally popular, while being aggressively mid, like peanut butter or Bruno Mars or brunch or Trader Joe’s or Vincent Van Gogh.)

My philosophy toward consumption is simple: Let people like the things they like.

Our time on this planet is limited, so I make a point not to judge people based on how they spend it. You should do what brings you joy, and so “taste” is irrelevant to happiness. In fact, there is a need for popular culture (as my friend Danni Patterson described here) and snobs are a cancer that create unnecessary division and enable repression.

I say all that as a caveat as we dive into the question of whether TikTok can give us art, because as so much of the commentary around “social media” is born of snobbery and “back in my day” generational judgments, it’s hard not to become the old man screaming at clouds when turning a critical eye on the fastest growing medium in humanity’s history.

Part One: A Brief and Simple History of Emerging Media

“We must expect innovations to transform the entire technique of the arts thereby affecting artistic invention itself and perhaps even bringing about an amazing change in our very notion of art.” -Paul Valery, 1928

I don’t think it’s a stretch to say that the most popular works of culture are usually not regarded as the highest quality by critics and social elites.

At any given point in history, the most popular media serve as a canvas for both popular entertainment and avant-garde artistic exploration. The highest-selling book from the 1920s is Ulysses, despite initially being banned for more than a decade in most of the English-reading world. The year it was published, 1922, pulp characters like Tarzan, Zorro, and John Carter of Mars were dominating “literature” and had millions more readers.

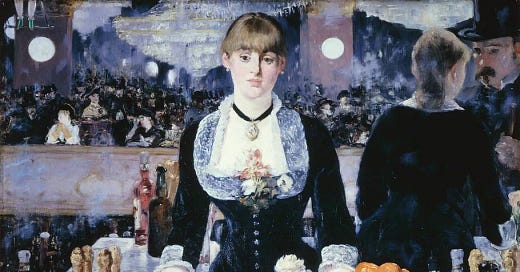

The most popular entertainment generally aligns with audience expectations and adds a slight element of novelty, while experimental works of art garner significantly less popularity (at least initially, in their own time) but exert influence over creators of more mainstream art. Gradually, popular tastes change and absorb (some of) the avant-garde’s innovations. As another example, Manet was roundly rejected in his lifetime and today is considered arguably the most influential artist of his century.

The balance between the broad stuff and the edgy stuff varies over the lifespan of media. When a new medium first achieves critical mass it is its broadest, least “artistic” version of itself.

After the invention of the printing press, the technology was used almost exclusively for the Bible and pornography for its first few generations. Going back even further, pre-historic cave paintings almost all depict animal hunting, which was, like, the NFL of the time.

Similarly, the early days of TV were populated by very basic talk shows and recreations of popular radio formats and low budget game and proto-reality shows.

Television eventually would give us Roots, The Sopranos, Atlanta, Ways of Seeing, and countless other shows that broke new ground and achieved varying levels of cultural permanence (in memory, watchability, or both). More importantly, these artifacts also inspired and influenced much of what came after. But we still also got trashy reality shows, wildly popular but formulaic sitcoms, and still more versions of unnecessary talk shows, because there is a need for trashy, low-brow entertainment to provide content sustenance for the masses.

To put it simply: Evolution of arts and entertainment (and, as a result, culture at large) requires the creation of works that are initially deemed offensive, radical, or unconventional. Without them, art would be replaced by perpetual kitsch.

Now that we’ve skipped our way through the history of communication and the role that artists have played as new media emerged, we turn to TikTok and its copycats.

Part Two: Personalization and Its Discontents

“Beauty is no quality in things themselves: It exists merely in the mind which contemplates them; and each mind perceives a different beauty.” -David Hume

At first, I thought the For You feed might free us. That personalized algorithmic content recommendations would, by removing our conscious choice, take our desire for social approval out of the equation. We could get what we truly want, instead of what we think someone of our desired social status would want.

It would also neutralize the limiting impact of cultural critics and curators by democratizing discovery beyond elites.

Could the personalized feed be the magic to free us from the yoke of cultural expectation? Might it finally change the spectrum from Good-Bad to Brings Me Joy-Doesn’t Bring Me Joy?

The answer is No.

We’ve simply traded one oppressive master for another, the elitism of the snob replaced by the tyranny of the algorithm. The snob’s judgment was benign, like a cranky grandparent who can’t understand all the newfangled nonsense. But the algorithm’s judgment is proactive and absolute, like the town government in Footloose, strict in ensuring adherence to norms.

As we explored in the previous section, the whole history of art is built on pushing beyond current expectations and aesthetic appeal, giving people what they didn’t want profoundly enough that they question why they didn’t want it in the first place. Societally, we’re a 6-year-old who doesn’t want tomato sauce with our pasta noodles because we can’t imagine anything better than butter.

TikTok, Insta, and YouTube, via advanced algorithms that prioritize engagement, keep feeding us buttered cut-up spaghetti with different food coloring, keeping us comfortably satiated and unchallenged.

In Filterworlds, author Kyle Chayka calls this algorithmic normalization: “Whichever content fits in that zone of averageness sees accelerated promotion and growth, while the rest falls by the wayside. As fewer people see the content that doesn’t get promoted, there is less awareness of it and less incentive for creators to produce it—in part because it wouldn’t be financially sustainable.”

If Ulysses was a TikTok video, it would top out at a couple of dozen views and disappear into the digital ether forever, and none of us would ever know of James Joyce’s genius or syphilis.

This isn’t the first time we’ve worried about a new medium’s stifling effect on culture. Radio, TV, video games have all come under attack from across the political spectrum before both fulfilling and transcending their doomsday prophets.

So what makes TikTok different?

There’s No Taste

In a TikTok, creators’ choices are atomized to serve the algorithm, consciously or subconsciously, because success is defined only via measurable interaction, not on impact on the viewer. As a result, quality is not only irrelevant, but also limiting. In Filterworlds, Chayka writes “The cultivation of taste is discouraged because taste is inefficient in terms of maximizing engagement.”

“Bad” content can be better for engagement than trying to be good and so unlike previous media, a lot of social media is made in bad faith.

I call them “debaits,” because they are simply baits to get people fighting:

The nonsensical math or logic problems that are written to have no definitive answer but get lots of people fired up about what it could be.

The intentionally unhygienic or disgusting recipe videos that people can’t help venting their fury at in the comments.

Obviously wrong or unhelpful “self-help”

The just-shy-of-hyperbolically-fake fake news.

The most engaging content in an algorithmic feed is the perfect combination of banal, bad parody, and insincerity.

If the Louvre ironically hung a purposefully poorly drawn drawing next to the Mona Lisa to make people angry and spur a debate about the nature of creative expression, you might consider it a wild piece of artistic ambition. If they replaced all the existing work with purposefully shitty stick figures and children’s finger paintings, it would just be a fancy building that wasn’t worth going into.

It’s All Promotion

One might point to the numerous artists who use social media to sell their work as evidence that it can house real art. But there is an important difference between art form and art promotion. Of course, TikTok can be used by artists to promote their off-TikTok work. But can TikTok itself distribute the art, in the same way that The Wire existed as an influential masterpiece in the same medium as Pimple Popper MD and the Cavemen sitcom?

Every TikTok account is defined by its numbers. And so, every post is an ad for the next post, every consumer engagement designed to induce the next engagement.

I think the single “genre” of Reels that encapsulates the state of social content are the “I was today years old when I learned you can swipe right to view a profile” videos. If you’ve spent any time in any social feed, you would have found something similar. A post that is about nothing but engaging with the post which you are already watching. It’s like if Nicole Kidman asked you to go back out to the lobby and come back into the movie theater in those AMC commercials.

Imitation without Imagination

All art is derivative.

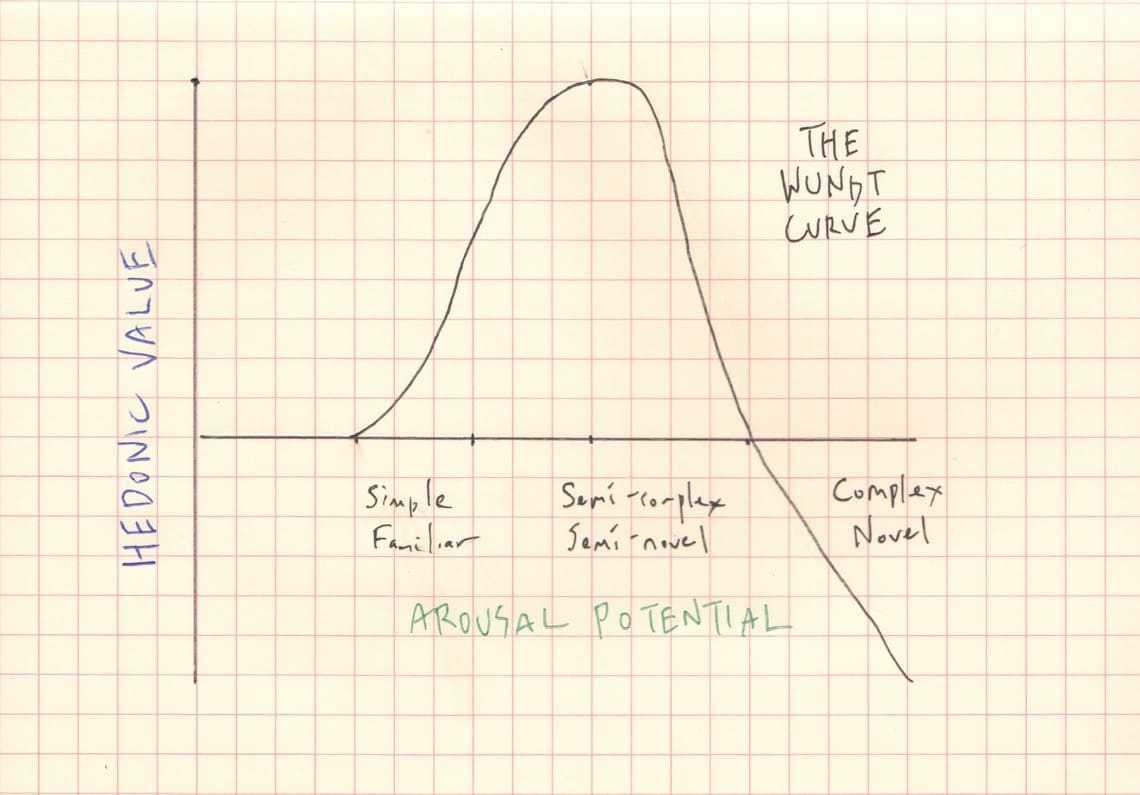

Human curators of the arts (whether Salon organizers, book publishers, or TV programmers) seek out work that adds novelty to the familiar because, compared to the overly familiar, novel works provide greater hedonic value, which is the value placed on an experience based on the emotional response it creates. This is demonstrated by the Wundt Curve below, illustrated below by W. David Marx.

Works that are too novel or unconventional don’t provide as much pleasure, and artists are continually testing the line to see where they can try new things without destroying hedonic value.

The algorithmic feed, in contrast, is like an entire industry inspired by the VHS knockoffs of Disney animated movies in the 90s. Copycatting is the business model.

In the judgment of the algorithm, adding something new to an existing concept carries only risk, which is why participating in a trending action or sound is the easiest way to drive up your engagement.

That word—participating—is the key. Artists by nature are builders, changers, rejectors. They take something that exists and do something new with it that, hopefully, only they could do.

But social media clout is predicated on participation. The creator participating in what’s already happening to get their viewers to participate via engagement. Deviation is not an option.

Without Context, There’s No Patina

The Odyssey was a foundational piece of art before it was ever written down. Something about the story and its telling compelled people to pass it down across generations, just like so many works of creation that have endured the passage of time. As these works survive the years, they remain relevant while gaining patina—the echoes of time that remind us that they come from a different age but remain relevant in the now.

You can feel this patina even in recent works in modern media—the flip phones of movies of the early aughts, the squared aspect ratio of TV shows from the 90s, the language used in any content before August of 2019.

Importantly, not only do we still have access to a lot of this content, but human curation helps to contextualize and organize it and, in time, give it permanence, make it canon.

But on TikTok, everything is transitory. It disallows discovery via the sheer pace of delivering content for today. Each video is its own moment between screen and viewer, intentionally ignorant of what might come before or after it, its ambition not to last, but to make the most of its few fleeting seconds. Odysseus’s sirens, digitized, not trying to play a part in the larger world but trying to make you forget about it.

Even musicians or stage actors whose art is ephemeral are creating experiences to be remembered, talked about, and made legendary. Being at a show is a moment for your memory and a proof of your participation in cultural canon. A demonstration of taste.

In the feed, speed replaces taste. High and low art has been replaced by early and late consumption. I’m not sure if this alone is a bad thing, but the problem is that it limits our power to discover based on our own moment. We can’t dive into an obscure TikTok video that mirrors how we feel because, if it even existed at all, the algo has already moved on.

All of these elements add up to an environment that is not only challenging for artistic ambition, but one that is downright hostile to it. Once we dispense with the trappings of art, have we dispensed with the art? Is the contextual fit the art itself?

And yet, millions of creative people continue to let the platforms shape their output in the quest to drive engagement.

Perhaps in asking if TikTok can distribute art we’ve answered the question of whether AI can create it. Maybe the “art” is not the posts and videos themselves but the creators behind them and viewers in front of them, and the artist is actually the algorithm that shapes them.

Maybe AI already has created art. But we’re not the viewer or the subject; we’re the work.

Interlude: So What?

As the unity of the modern world becomes increasingly a technological rather than a social affair, the techniques of the arts provide the most valuable means of insight into the real direction of our own collective purposes. -Marshall McLuhan

A logical question at this point might be “Who fucking cares?” So what if TikTok and its copycats can’t give us art?

For one, feed-based media is increasing its share of our collective entertainment consumption time. And worse, a massively increasing portion of “creators” are defaulting to TikTok as their medium of choice. According to Morning Consult, 86% of young Americans say they could see themselves as influencers. The dream symbolized by a bus ticket to Hollywood has been replaced by one that starts on a Sign Up screen.

Plus, the “For You” model is increasingly influential beyond just TikTok, Insta, and YouTube. All the streamers are using algorithms to goose engagement and inform programming choices. And producers of Hollywood-level content are conscious of creating meme-worthy moments, from Baby Yoda to the Ken Song to almost any new music that reaches the top of the charts.

Even the Met Gala, supposedly representing the height of couture and located at one of the world’s most decorated art museums and populated by some culture’s most admired people, is consumed primarily in snippets that are algorithm-friendly and decidedly context-less.

So while it might not seem that big a deal that TikTok will never provide us a Manet or Tom Waits, it matters as more consumption and creative aspiration being directed towards these platforms necessarily means the creation of less art overall, and artistic expression and experimentation is a critical driver of societal and cultural progress.

Part Three: I’m the Problem, It’s Me

“It is not important to make many pictures but that I have one picture right” -Piet Mondrian

Which brings us to the advertising industrial complex in the room. Well before ad networks and algorithmic bidding and contextual targeting, Jean-Francois Lyotard forecast the troubling expectation that advertising would become intertwined with entertainment. That intermingling has reached its apex: Social media is the first form of artistic expression that is entirely ad-driven.

Because we have choice in watching a film or reading a book, not every component of the work is commercially oriented; not every choice the artist makes is designed for selling. Many might be (like casting Leonardio Dicaprio instead of a more talented, unknown actor), but many are also made because they serve the art better.

You can’t really blame the platforms for giving advertisers exactly what they want: endless engagement. And you can’t blame advertisers for following their audiences as they migrate screens. But as we’ve already talked about, when all original content on the platform is shamelessly promotional, so brazen in its attempt to manipulate the algorithm, the ads contained therein exist in a weird, uncanny valley of meta-consumerism.

Even videos or posts that are officially social media ads are nearly indistinguishable from the “organic content.” Julia Alexander identified the main difference between the old advertising world and the social ad world as “the conceptual understanding of something being sold to you versus something just appearing on your feed. We intrinsically know when an interruption is happening; when something ‘cuts to commercial.’ It’s far more difficult when the entire app is a blended commercial.”

But if advertising is the driving force behind the artistic degradation cause by these platforms, it is also its biggest victim (well, after democracy, mental health, a woman’s right to choose, and any sense of hope in humanity).

The allure of these environments for advertisers (aside from the massive amounts of consumption shifting to these platforms) is the theoretical ability to reach highly selected audiences with highly selected messages.

I say theoretical because so-called personalization has not proven its value to marketers yet. It HAS proven its value to the platforms selling advertising space to those marketers, though. Personalization certainly drives greater engagement, creating greater consumption and more opportunities to sell ads. Even the ads themselves are now self-judged on engagement (Meta has trained every performance agency to parrot their favorite talking point that “creative is the new targeting”)

Ironically, the more personalized things get, the less choice we (as consumers) have. How can a platform’s content really be personalized when all said content is created to engage as many people as possible? And if advertising assets need to play by the same algorithmic rules as that content, what value is a differentiated message?

Let’s play it out:

Consumer businesses want to create strong brands to set themselves apart

Brands (often) depend on paid advertising to create that distinction at scale

Platforms utilize algorithmic personalization to encourage people to spend more time so they can sell more ads

That personalization rewards both content and ads that conform to the existing normal

Brands must conform to the current normal

All brands are the same.

If you zoom out even further, it looks like this:

Advertising exclusively fuels the most addictively engaging content consumption engine ever. ———> Advertising becomes increasingly useless.

The snake eats its own head.

Part 4: What Does It All Mean?

“Everybody starts to lose control / When the music is right / If you see somebody hanging around / Don't get uptight” -Lionel Richie, “Dancing on the Ceiling”

A healthy cultural ecosystem is built on stratification of consumption from high-brow to low-brow and from mass to niche. The algorithmic For You feed threatens to overwhelm a millennia-old cultural development process. I fear this will mean fewer creators making art for art’s sake, fewer people exposed to new ideas through that art, and a slowdown in the exchange of those ideas that make the world a better, more interesting place.

But even worse, it will create a difficult ecosystem for advertisers to build a brand!

A hopeful view: by consolidating our basest consumption and grossest commercialization to social media, maybe the lamented media formats of old can return to pure art form, commercially optimized for maximum taste, rather than mass appeal. Just as the popularity of opera “declined” to become a mark of aristocratic distinction as mass media grew to dominate culture, maybe movies, TV, and even the written word will be consolidated around a greater quality they couldn’t have achieved in their dominant days. Sure, this will mean a contraction in the size of today’s entertainment industry, but that is fait accompli.

Large-scale entertainment with higher artistic ambitions is already growing more commercially viable. Barbenheimer, Inside Out 2, and Dune are all, despite still utilizing IP, much more unconventional and challenging than blockbusters of the 90s, 00s, or 10s.

Maybe we will fully compartmentalize our entertainment lives between consumption and inspiration, between sustenance and nourishment? Guy Fieri and Creed and Pimple Popper (or their equivalents and copycats) will find their rightful place in our ad-supported algorithmic feeds as part of a reconstituted “mainstream” media while the more costly endeavors like feature films, “TV,” and music evolve to be more creatively ambitious in notably less volume and we see a new renaissance for experiential, analog creation via painting, sculpture, stage plays, immersive experiences.

A steady stream of exactly what we need interrupted by briefer, more special moments of exactly what we might not.

Part of being human is the urge to create. Our collective artistry cannot be stifled. But maybe it will have to retreat from the forums of mass media and return to the more intimate vessels of pre-modernity.

Epilogue: Another Option

Freedom of Speech was a modern notion to accompany the rise of liberalism and published media. But now, in the postmodern world, it’s not enough, both because the digital platforms are more powerful than any liberal democracy could ever be, and because freedom of speech is meaningless without the power to be heard. It’s time for the 28th amendment: freedom of discovery.

Short of an update to the constitution, legislation that requires an option for a non-algorithmic feed would at least give us the opportunity for self-discovery. (This brings up questions of free speech, but as the platforms have argued that they are not publishers, they need not be regulated as such.)

I started this epic saying we need to let people like what they like. But if they can’t exercise any curiosity, how would they ever know?

Also, don’t forget to like, comment, and share!

This Week’s Whimsies (All Further Explorations from Today’s Topic)

A great clip (from a mediocre movie) about letting people like what they like.

A deep dive into digital creators’ originality problem from a digital creator, who explores the “fine line between copying a video and participating in a trend.”

A couple of counterpoints: This creator might just be making art on TikTok ($) and this piece from 2022 argues “TikTok is the Next Generation Art Platform”

This great piece by Blaise Lucey gets into all the terribly dark things that happen to participants in creator “hustle culture”

This 1928 essay by Paul Valery could have been written in 2008 in how well it illustrates the challenges and dangers of ubiquitous media.

I really enjoyed this breakdown of what a healthy culture looks like, especially because it came to a different conclusion than I did.

As you could tell, the writing of W. David Marx was very influential to this piece, so I highly recommend subscribing to his newsletter about culture.